BODIES

The Body in the Classroom

BY SOWON PARK

sowonpark@ucsb.edu

I. Are you triggered?

Warning!

Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart: Racism, Misogyny, Suicide, Colonialism, Religious Persecution.

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice: Classicism, Alcohol Consumption, Misogyny.

These are a couple of examples taken from the Trigger Warning Database, which provides hundreds of categories of recommended disclaimers for fiction.

Many see the increased requests for, and the prevalent use of, such warnings as emblematic of a new “safetyism” in education and the occasion for lamenting that students are too easily distressed and too avoidant. What students actually need, as Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff argued in The Coddling of the American Mind (2018), is a healthy dose of stoic forbearance, not infantilizing over-protection.

From this perspective, it is only sensible to ignore warnings on literature were it not for the persistence with which students continue to demand them. And such insistence on the need for trigger warnings can be triggering to faculty.

There is another reason why trigger warnings can spread consternation. They are perceived as a form of speech regulation. The worry here is that trigger warning requests encroach arbitrarily on professorial autonomy, which may intrude into academic freedom. If left unchecked, there is a danger of trigger warnings becoming normatively pernicious and standards will be compromised. Members of academic community who have sat on various committees will recognise this as the “Principle of the Wedge” argument (9).

Both concerns are valid, and shared, at least in part, by the researchers at the Trauma-informed Pedagogy (TIP) project at Literature and Mind. We believe in, and are committed to, building student capacity to withstand discomfort in order that complex intellectual problems can be tackled, just as we are committed to upholding academic freedom and maintaining high standards. These are necessary parts of any pedagogy, trauma-informed included.

What we wish to bring to a wider discussion is the severity of the underlying issues that give rise to requests for trigger warnings. Because exasperation and defensiveness deflect from rather than engage with them. They are mis-engaged reactions that tell us less about what’s going on for students, than about the difficulty the faculty face in imagining what it’s like to be the kind of student who requires forewarning.

At the back of these reactions is a perception that trigger warnings are unique to Generation Z, widely characterized as the “unhappiest generation” ever. But the desire to be mentally and emotionally prepared for difficult material is not exclusive to contemporary youth, unhappy or not. Well before trigger warnings entered the discourse of higher education, Susan Sontag, writing in Styles of Radical Will (1967), explored the idea of “psychic preparation,” though in a different context.

This essay revisits Sontag’s query in order to grapple with a more fundamental set of questions, ones that are resonant in our current transitional moment: does learning today require a certain form of mental and emotional preparation? And if so, why? And what forms might such preparation take?

2. The Enduring Fantasy of the Disembodied Mind

Before turning to the topic of mental preparation, a central feature of the debate around trigger warnings warrants closer examination. That is the chronic disowning of emotional and mental vulnerability in academia, where learning continues to be framed as the pursuit of a purely rational, disembodied intellect, in which emotions, physiology and personal history have no place, and where psychological vulnerability is cordoned off from notions of academic rigor.

This narrow conception, reminiscent of the Victorian don, found superb representation in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927), where Mr. Ramsay is described as possessing such a mind:

It was a splendid mind. For if thought is like a keyboard of a piano divided into so many notes or like the alphabet is ranged in twenty-six letters all in order, then his splendid mind had no sort of difficulty in running over those letters one by one, firmly and accurately, until it had reached, say, the letter Q. He reached Q. Very few people in the whole of England reached Q.

Rational inquiry in this novel is characterized as measured, linear and impersonal. There was admiration, even awe, for the relentless drive of what Woolf sometimes called the "Apostolic Mind"—a will to think one’s way through, letter by letter, to the furthest limits of abstraction while suppressing all other processes of the mind. This model is still idealized in academia today.

But Woolf also made it clear that this model of mind is corrosive and unsustainable. It isolates, exhausts, and depletes. It can also harm.

Today, we are witnessing the real-world consequences of upholding this model of mind within a radically changed cognitive environment—one that, over the past two decades, has expanded into and been reshaped by the internet and lately by generative AI.

Recently, Jonathan Haidt appeared to walk back on his 2018 “coddling” thesis with The Anxious Generation (2024). Here he argues there has actually been a “great rewiring of childhood.” He explores the consequences of smartphone-based adolescence and identifies algorithm-driven platforms like Instagram and TikTok as disruptive to attention building and emotional resilience. Whereas he formerly upbraided the intellectually fragile academia in The Coddling, he now sees social media as the primary cause of today’s “hostile learning environment.”

He is far from alone in thinking so. And it is not just the youth whose cognitive habits have said to have been altered by technology. Betsy Sparrow’s 2011 landmark research on the cognitive consequences of digital technology found that having access to search engines such as google makes all of us less likely to remember facts and more likely to remember where the information can be found. (Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips) Studies on decline in spatial memory through extensive GPS use is well established. (Habitual use of GPS negatively impacts spatial memory during self-guided navigation)

A comprehensive account of the cognitive consequences of technology and their impact on higher education lies beyond the scope of this discussion. But one downstream effect of the current cognitive environment is pertinent to the issue of triggers and traumas.

In the classroom the traditional intellectual imperative of the disembodied Cartesian mind has materialized albeit in a grossly ironic form. For many “digital native” students, their online identities and personalities can feel more authentic and essential than their real-life selves. In this context, the dissonance is sharp when students enter the classroom as living, feeling, actual bodies. A substantial psychological adjustment may be required simply to participate in a classroom where hundreds of students sit, front-facing, in tiny uncomfortable seats, and where the expectation is detached intellectualism, even as the world is eroding the pre-conditions that enable such lofty detachment.

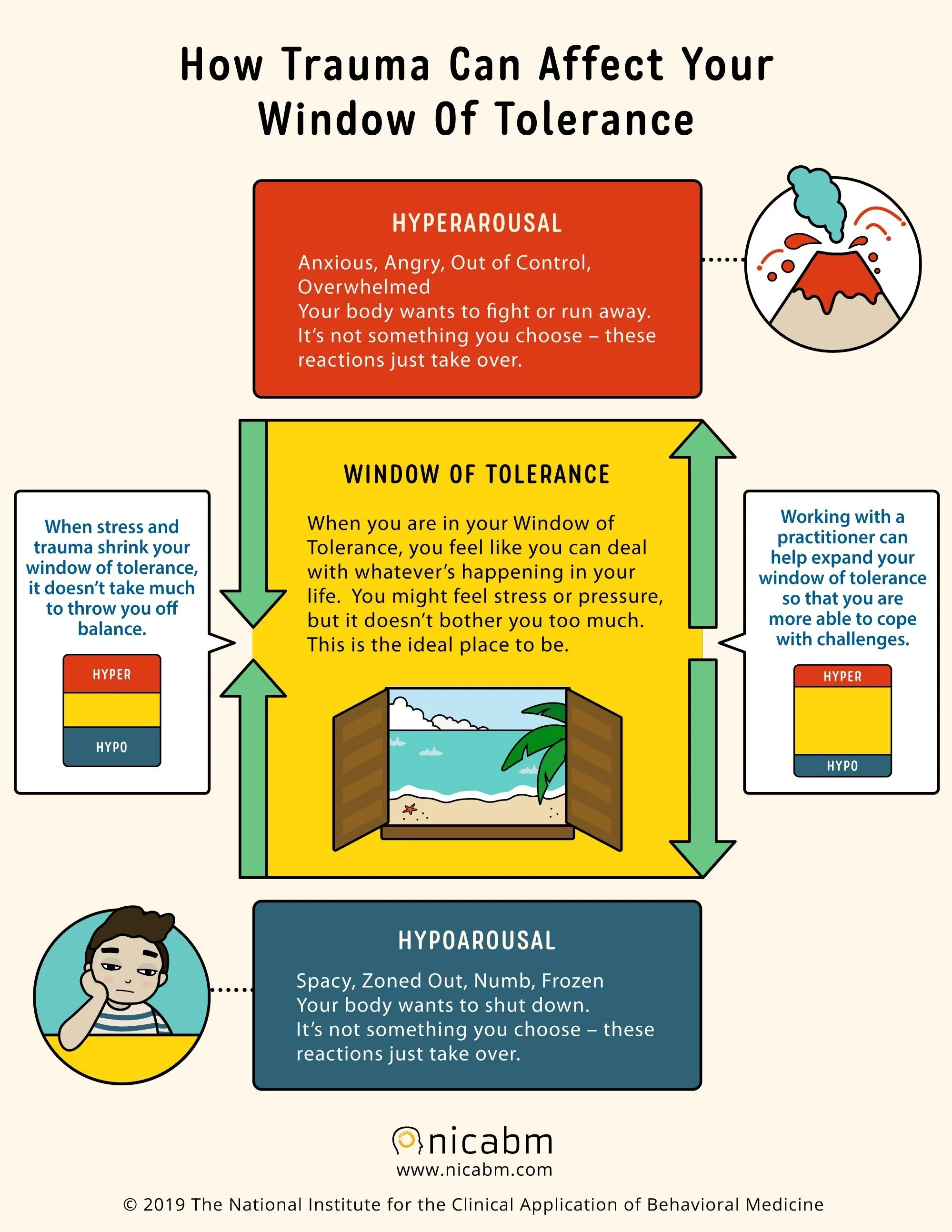

There is a concept called the “window of tolerance” introduced by the psychiatrist Daniel Siegel (The Developing Mind 1999), a leading figure in the field of interpersonal neurobiology. It is a metaphor for the optimal zone of mental state in which a person is able to function most effectively. From a nervous system perspective, you're able to think clearly and manage a range of emotions when you're “within” your window. You can also respond to challenges. When you are out of this window however - as either hyperaroused (anxious, angry, overwhelmed) or hypoaroused (numb, disengaged, frozen) - you become incapable of reflection or connection.

A great number of students today come to class anxious, overwhelmed or shutdown – that is to say, in a dysregulated state, and are expected to be Mr Ramsay. Placed in this context, the growing demand for trigger warnings directs our attention to deeper questions—questions that higher education can no longer afford to sideline. When students boycott novels that they find triggering, file complaints about “problematic” texts in course evaluations, request accommodations through CARE or DSP systems, display agitation during class discussion, mentally shut down, or withdraw entirely from participation, these are not merely disciplinary problems or generational quirks. They are signs that the cognitive and affective environment of higher education has changed. And with that change, the “window of tolerance” that traditional pedagogy once so casually assumed has narrowed. We are being called to adjust, not because the standards are lower, but because the realities are quite different.

Technology is but one cause of this shift. (see Julie Carlson’s essay “Relations”). Taken together, the pedagogic landscape is one where a mental health crisis has reached undeniable severity. Over 60 per cent of college students have one or more mental health problems, a nearly 50 per cent increase from 2013. Rates of anxiety and depression more than doubled between 2013 and 2021. Beyond the rising numbers, the range of conditions has also widened. The percentage of students diagnosed with ADHD has grown from about 4 percent in 2012 to nearly 15 percent today. Diagnoses of autism, AuDHD, PTSD, body dysmorphia, and co-occurring substance-related disorders are also increasing at an alarming rate. Mental health issues can no longer be bracketed, minimized, or treated as peripheral.

The emotional and psychological toll of academic life in this new cognitive environment demands that we rethink what constitutes academic rigor, and what the necessary preparations are that enable students to meet them.

III. The Real Reason Trigger Warnings are Problematic

Encounters with “triggered” students are now routine for faculty in literature and related fields where emotion and personal history come into play with rational argument and logical reasoning.

Obviously, no professor of literature sets out to inflict distress on their students. In most cases, faculty go to great lengths to prevent upset in class. But it is not always self-evident to a teacher what might and what might not be triggering to a student in a class of 150. Many teachers understandably deselect texts that have the potential to trigger students after an “incident.” But second guessing the triggering potential of literary texts is haphazard at best.

To give one example of the situation: when, say, the Nobel laureate, J M Coetzee’s Disgrace (1999) - frequently included on top 100 most influential novel lists and taught widely all over the world - is selected for a course on World Literature, the aim might be to examine the conditions of possibility for redemption in post-apartheid South Africa. But intentions aside, student survivors of sexual assault may be deeply crushed by the characterization of Melanie who is stalked and sexually exploited by her professor, David Lurie, because of the way the novel focuses on the plight of the Professor, reducing Melanie’s trauma to a mere backdrop to his internal moral dilemma.

Blaming the survivor student in this instance for her “fragility” is not a fair response. It is also an evasive, even irresponsible, response, since, according to RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network), the largest anti-sexual violence organization in the US, 26.4% of female undergraduates and 6.8% of males undergraduates experience rape or sexual assault. The vast majority of them do not receive restorative justice. Likewise, students struggling with personal traumas arising from racism, violence, or developmental neglect may find the novel anxiety-provoking or even retraumatizing if the novel is discussed only from the perspective of the protagonist and never from the viewpoint of his victims.

The answer is not to drop such classics from the reading list. Student survivors actively seek out courses that explore themes related to their trauma, drawn by the possibility that literature might help them make sense of their pain and fear. Avoidance of difficult material not only denies students this space, but brings disengagement on the part of both the teacher and student. It is an extremely costly tactic, exacting a high psychological price on all concerned, generating feelings of apathy and shutting down conversation.

To avoid controversy, minimize complaint and avoid upset, the easiest path might be to slap warnings on “sensitive content” and to carry on. Even if one is skeptical about the idea that some students may be “triggered” by reading fiction, one can appreciate that forewarning has the appeal of simple expedience.

But how effective are the categories given on the Trigger Warning Database with which this essay began? Empirical research suggests: not very. Richard McNally, author of Remembering Trauma, summarized in the 2020 paper “Helping or Harming? The Effect of Trigger Warnings on Individuals with Trauma Histories”: “We found no evidence that trigger warnings were helpful... We found substantial evidence that trigger warnings counter-therapeutically reinforce survivors’ view of their trauma as central to their identity”. In short, trigger warnings may be “functionally inert”.

Even more troubling, some studies suggest that trigger warnings may actually increase distress. This claim rests on four interrelated observations:

Viewing trauma as central to one’s identity can intensify PTSD symptoms. Trigger warnings reinforce this centrality.

Drawing attention to traumatic memories can prolong distress by reconsolidating negative associations.

Trigger warnings portray traumatized people as fragile, undermining their resilience and self-confidence.

They increase distress in those who already believe words can do harm—making literature students, in particular, a vulnerable group.

Nevertheless, trigger warnings have now become a managerial answer, operating as a kind of consumer information service that apparently protects both professor and student from mistaking triggering material for the non-triggering kind. It is a straight-forward risk management measure, a means of hedging against being punitively handled by the university authorities should there be an escalation.

As such, trigger warnings attend less to the problem than the institutional management of the problem. Consequently, reductive warnings of content and avoidance of certain words have just become part of the bureaucratic language that many people have learnt to ignore, even as student distress continues to rise.

IV. Toward a Trauma-Informed Education

The debate about and the failings of trigger warnings point to the deeper problem mentioned earlier: a structural blind spot in US higher education that arises from the persistent notion that learning is purely cognitive, divorced from the emotional and somatic realities of student life. Triggered students remind us of what higher education has long neglected, the embodied, affective nature of learning.

This is painfully apparent in literary studies, in particular. Novels are not self-enclosed entities any more than students are hermetically sealed off from the society in which we live. Many students bear the scars of social and economic inequities, domestic, interpersonal and community violence, displacement by political unrest, and identity-based bullying. Most students bring to textual criticism the strains of our society even while they try to measure up to the cultural imperative to appear ‘normal’. But to think that ‘normal’ lives are free of trauma is a classroom myth. What is needed is a reversal of the perception to see triggered students not as the problem but rather as a symptom that breaks open the smooth erasure.

How, then, are classics like Disgrace to be taught with the aim of serving all students? This is precisely where trauma-informed pedagogy becomes valuable—not merely as a strategy for managing classroom crises, but as a framework for reimagining humanist, literary education.

If we accept that traumatic experiences are not exceptional but prevalent, a different perspective on trigger warnings emerges. A forewarning is not intended to protect students from confronting painful truths but about challenging the erasure of trauma.

Our society values humans who show no injuries. We call them brave. We call them strong. And no doubt many of them are. The flip side is that this value often penalizes the injured, so there is inevitably shame and fear in recognizing one’s vulnerabilities. Perpetuating this hierarchical binary is the opposite of encouraging resilience and growth. Acknowledging the existence of trauma in our students is not to reinforce their weakness; it is to address the injuries they carry but feel they have to disguise.

When used sensibly in conjunction with a broader set of trauma-informed practices – ones that do not reinforce trauma-centrality - trigger warnings can serve a necessary function.

For survivor students, a forewarning offers a vital space for mental and emotional preparation. It gives them the preparation time to gauge the amount of mental and emotional discipline they need to instill in themselves to endure the disturbance they may have to face in dealing with certain issues. It eliminates the dread of being ambushed by content they are not yet equipped to confront.

More importantly, we signal to our survivor students that they are not alone—that their presence, courage and perseverance are seen. The sheer grit it takes to stay in the classroom, to keep reading, to keep thinking and engaging. It’s not about shielding students from difficulty, but about recognizing the demonstrable courage it takes for many students to engage with what they habitually disown and mask.

In the groundbreaking study, Trauma-Informed Pedagogies: A Guide for Responding to Crisis and Inequality in Higher Education, edited by Phyllis Thompson and Janice Carello (2022), Jeanie Tietjen argues that education must be considered in a holistic context. It says a great deal about our era that such an fundamental point must be made. And yet it is incredibly powerful to read her words:

To be clear, trauma informed education does not mean that faculty and staff diagnose students as patients: the educational alliance is fundamentally different from that of a trained, professional clinician. Being trauma-informed in higher education means that every area of the educational community—from pedagogy to campus security, advising to financial aid, facilities to college policies and administration—can be informed by understanding: the basics of the learning brain, the prevalence of trauma, adversity, and toxic stress, how resilience as skill can be encouraged through best practices and meaningful supports, and evidence that just one relationship can powerfully bolster productive and resilient behaviors. Rather than a rigidly prescriptive list of teaching or institutional practices, trauma-informed education instead describes a perspective or lens through which practices are evaluated and refined, revealing ways in which policies and practices might unconsciously exacerbate trauma, and pursuing academic rigor and inquiry in a supportive community informed by knowledge of lived experience. (122, emphasis mine)

The “Trauma-Informed Teaching Toolbox” in the volume, compiled through the insights of thirteen professors, offers a range of equity-centered, resilience-focused practical tools that address course policies, content design, and classroom discussions (see Aili Pettersson Peeker’s essay on Teaching at UCSB). These tools are not meant to impose a one-size-fits-all solution, but rather to provoke reflection and dialogue about how we teach. Personally, I have found many of these ideas invaluable for reflecting on how my own teaching aligns with the principles of mutuality, empowerment, and safety, as well as with the aims of building capacity to tackle emotionally challenging material, and maintaining excellence, especially in moments of high classroom anxiety.

V. Addressing “Disenfranchised” Trauma in Higher Education

Whether you support the idea of a 'trauma-informed' university will depend a lot on what you count as being “traumatic.” On this, there is wide disagreement.

Not so long ago, trauma was a concept confined to the psychological aftermath of extraordinary life-events, such as combat, surviving terrorist attack, and violent rape. These people suffered from PTSD because they had been through what some people now call “big-T trauma.” And since people affected by extraordinary events are by definition rare, trauma-informed pedagogical approaches in higher education are seen to be unnecessary.

However, over the past decade, this understanding has expanded significantly to include what is often referred to as “small-t trauma” or chronic and complex (that is, developmental) trauma. These experiences are not life-threatening in isolation. But have a cumulative effect on the nervous system and arise from a wide range of sources, including emotional abuse, chronic neglect, harassment, racial discrimination, climate anxiety, COVID-related disruptions, and other stressors that provoke sustained fear, instability, or helplessness.

The shift in understanding is in no small part due to developments in how trauma is understood biologically – which primarily focuses on the impact of trauma on the autonomic nervous system, or, in the words of Bessel Van Der Kolk, “the body keeping score.” Trauma, in this view, is not simply psychological; it is physiological, encoded in the body. To summarize: when a person’s existential sense of safety is ruptured, the autonomic nervous system is sensitized, producing either a hypervigilant state (“hyperarousal”) which may lead to an overestimation of the level of perceived threat, or a state of freeze (“hypoarousal”) which underreacts, is shut-down and collapsed – going outside the aforementioned “window of tolerance.” The key takeaway is this: both states greatly reduce one’s cognitive capacity.

The neurobiology of trauma has provided the TIP project with extremely useful frameworks for understanding students’ emotional and cognitive capacity to engage with learning. When students are in states of hyperarousal (triggered, panicking, enraged) or hypoarousal (dissociated, shutdown, disengaged), their behavior can be misread as disinterest or defiance.

This takes us back to concerns about the perceived overuse of the term "trauma": do we risk diluting the specific meaning of "trauma" and in turn, end up labelling everyone as traumatized to some degree? Moreover, does this lack of differentiation between big-T and small-t trivialize the experiences of those recovering from what some would call “real” trauma?

A problem with trying to differentiate between “big-T” trauma and “small-t” trauma is that the cause of dysregulation —whether monumental or cumulative—does not correlate predictably with the symptoms it produces. Many soldiers return from war without developing PTSD; some even thrive on the experience. By contrast, others may experience profoundly dysregulated states from cumulative, often less overt stressors. Clinically speaking, PTSD is diagnosed not by assessing whether the cause of trauma is "deserving" but according to five specific criteria based on the symptoms, not the scale or nature of the trauma itself. Only one of these criteria pertains to the source of trauma, which can be either direct or indirect exposure to threat. The other four criteria focus on the persistence of intrusive thoughts, avoidance of thoughts, alterations in cognition/mood, and hyperarousal.

Which is to make the point that the binary of big and small trauma is not a clinical distinction. In 1989, clinical sociologist Kenneth J. Doka proposed the concept “disenfranchised grief” to refer to forms of grief that are not socially acknowledged, sanctioned or publicly mourned. (Disenfranchised Grief: Recognizing Hidden Sorrow) We could apply Doka’s concept to forms of trauma that are similarly “disenfranchised.” Disenfranchised traumas are those that are not publicly accepted or sanctioned. They are often dismissed or are unseen. Sometimes, there are penalties for acknowledging them. Discussing the differences between socially sanctioned trauma and “invisible” trauma, Sophie Lefitz, a student at UCSB, wrote:

In real life, I’ve noticed that trauma hits differently for women than it does for men, not just in how it feels, but in how people respond to it. When women talk about what they’ve been through, we’re questioned. We’re picked apart. Did we lead someone on? Did we say “no” loud enough? Were we being too dramatic? It makes you second-guess everything. But when guys go through something, people usually believe them right away. Their pain is taken seriously. And that doesn’t mean they don’t hurt, it just means the world is quicker to see it and validate it. … It’s like, if you don’t bleed, if there’s no visible mark, people think it didn’t really happen. That kind of invisibility is its own kind of pain. That’s the thing I notice most when I compare male and female trauma in books. The way female trauma is often quiet. Hidden. Dismissed. Or romanticized. It’s not always about war or beatings. Sometimes it’s about not being believed. Not being heard. Being touched without consent. Being told you were “asking for it.” Or “it wasn’t that bad.” Or “he didn’t mean it like that.” Meanwhile, male trauma is often loud and visible. A fight. A fall. A loss. And I’m not saying it hurts less, it just looks different. It's told differently. And that difference matters.

The lens of disenfranchised trauma helps us recognize the diverse and complex ways in which trauma manifests. When students are dysregulated, overwhelmed, or struggling - in “fight-or-flight-or-freeze” mode - the educationally appropriate response is to acknowledge their experience and respond with fitting compassion and understanding, regardless of whether the trauma is acute or chronic. The classroom is not the place to adjudicate the legitimacy of one student’s suffering over another’s.

VI. Why call it “Trauma” and not “Mental Health”?

The decision to frame this initiative in terms of trauma rather than mental health is intentional. The aim is not to equate and conflate distinct psychological conditions—PTSD, depression, anxiety, OCD, and others—each of which has different causes, symptoms, and treatments. But being informed by the physiology of “trauma” provides a useful somatic framework for dealing with conditions far beyond it.

Despite the real differences, what students with these conditions share in the classroom is heightened mental stress which overloads the autonomic nervous system. A somatic approach to trauma provides a frame for understanding of how neurophysiological dysregulation produces threat-based responses that are survival mechanisms - commonly described as fight, flight, fawn and freeze. Acquiring the ability to recognize and respond appropriately to highly charged states, including less visible ones like “functional freeze” or shutdown, can be a crucial component of humane and effective teaching.

One of the most relevant concepts from somatics-based trauma studies in this context is titration: the principle of slowly and incrementally increasing exposure to emotionally intense material, much like adding one liquid to another drop by drop. In pedagogical terms, this means guiding students to develop tolerance for difficult emotions by gradually building up to intense scenes or topics, offering time, space and support to pause, reflect, and ground themselves along the way. Many studies now indicate that traumatic content, when unaccompanied by mitigating processes, have detrimental emotional impact on student learning. Some have called this “risky teaching”; others, “perilous pedagogy.”

Central to preventing re-traumatization is introducing students to small, manageable amounts of distress while allowing them to let their nervous system to settle and regulate in manageable increments. Reader-response exercises that emphasize phenomenological awareness, such as inviting students to pay close attention to changes in their embodied reaction, can allow for intellectual development that is not separate from the emotional. And the cultivation of the awareness of one’s emotional or embodied response is what builds the capacity to remain present and reflective in the midst of intellectual difficulty. (see Emily Troscianko’s essay on process in writing) Titrated exposure may at times involve risk, stumbling and uncertainty as part of the learning process but it avoids overwhelming students who have not yet built the capacity.

Literature triggers deep feeling in all of us. A novel is not an Actuarial Science textbook. The range of reactions that fiction elicits necessarily includes discomfort. Often there is devastation. Because reading can disclose realities that people habitually repress as the price of perpetuating normality.

If the goal of education is not merely to produce analysis, but to grow capacity—for critical thought, for emotional resilience, and for the kind of empathy that makes both scholarship and citizenship more humane - triggers and traumas must be addressed.

And when addressed, the effect can be much deeper than one can imagine for both student and teacher. One of the best articulations of this effect is captured by Andrea Alexander, who writes:

“(The) shift, from “my” to “our” course, is the best way I can summarize what happened. I didn’t fear my students or dread going to class; I was excited to teach again.” (Trauma-Informed Pedagogies, 77)

Not fearing our own students and not dreading walking into class may seem like the basic minimum for any teacher. Yet, in practice, even these can sometimes feel out of reach. In these moments, we need reminding that feeling both excited and deeply rewarded for teaching, simply for its own sake, is not an extravagance but a necessity, something we should actively work to preserve.