WRITING

BY EMILY TROSCIANKO

emily@troscianko.com

Experience-Informed Writing

“The beautiful part of writing is that you don’t have to get it right the first time, unlike, say, brain surgery.” (Robert Cormier)

1 Setting the scene: On trauma-informed pedagogy and experience-informed writing

Any robust incarnation of trauma-informed pedagogy must involve supporting students to develop practically applied self-knowledge. If individuals are not being helped to develop and exercise practical wisdom about their own state of being and its relation to their academic work, then they are not being helped to study.

One strand of professional expertise on which I’m drawing when I say this is my work as a coach. In the coaching context, it is a truism that individuals are unlikely to change unless they know what they want, and that an articulation of “what I want” is stronger when it includes not only negations (I want to be free of) but also positives (I want to be free to). As UCSB-specific data that I’ll be sharing here have indicated, when invited to turn their minds this way, most individuals are able to readily articulate their writerly dreams—and those dreams have everything to do with their dreams for the rest of their life.

I therefore like to think of what I’m doing in this domain as “experience-informed writing coaching”. “Trauma-informed pedagogy” as a label reminds us of how wrong all this can go if we don’t address the life around the work, or if we address it badly. There can also be positives for individuals in explicitly naming their trauma, as part of what’s needed to work with it, not against it, and prevent its damage from continuing into their future. But “experience-informed writing” gestures more directly towards how good all this can get if we bring process-directed curiosity to our professionally creative lives.

My time at UCSB hosted by the Literature and Mind Center and the Trauma-Informed Pedagogy project has made enjoyably clear that experience-informed writing aligns with the core values and practices that characterize the UCSB-specific style of trauma-informed pedagogy. My time here has also been a great opportunity to refine this meta-method further, and to theorize it more than I had before. Incorporated as one strand of this evolving style, experience-informed writing helps TIP at UCSB convey 1) that process matters, and 2) that being guided by the kind of experience one wants to have is a reliable way of getting processes to be smoother and more successful. In turn, this helps students get curious about the act of writing—or rather, the many varied actions that comprise it. And this is probably the only way to divest writing of its status as something to be mystified, feared, and avoided—qualities that wrap it into a maelstrom of habits and emotions that effectively block creativity and clarity. Once writing feels like something ordinary, mostly pleasant, and sometimes even exciting, it can realize its potential as a powerful tool for both communicating and thinking (and getting through university). It can do so all the more dramatically for those experiencing or healing from trauma, or whose baseline is for any reason one of instability and/or disempowerment, because this is all about cultivating their opposites.

In what follows, I’ll set out what exactly I mean by experience-informed, taking academic writing as the application area. I’ll also summarize some of the UCSB-specific evidence that allows me to say confidently that this is an approach that works.

2 The problem of writing reliably: How (and how not) to solve it

Contrary to the old tortured-artist clichés, it is a fairly reliable truth that if things aren’t going well in your life, things probably aren’t going well with your writing. Writing is—especially in the academic context—an intellectually demanding activity that requires time and concentration and typically has long-deferred rewards, and therefore a standard way for writing to go is not at all. At the best of times, emails, meetings, groceries, taxes expand to fill the space we allow them. And when times are harder, they do so even more readily. When we don’t feel well, planning well is harder, thinking clearly is harder, and avoiding the difficulty and discomfort that often come with thinking clearly is even more appealing than usual. Avoidance increases fear and also means that once writing does begin, the deadline is usually uncomfortably close, which makes writing feel even worse, hence breeding more avoidance for next time.

It’s easy for universities to ignore these dynamics. Even though writing is one of humankind’s most powerful tools for thinking and therefore one of the most crucial skills for most students to acquire, and even though writing is the primary currency of academic progression, it’s easy for instructors and advisors to concentrate on the content and assume that the processes will take care of themselves. My home institution, the University of Oxford, has an illustrious 800-year tradition of doing this, and it works less well every year.

So, what works better? In short, taking process seriously. Which means taking experience seriously, because attending to experience is our surest guide to getting processes good.

New Year’s writing bootcamp* for the Baillie Gifford Writing Partnerships Programme, Humanities Division, University of Oxford, 2019

*(I ditched the military metaphor a couple of years later!)

Beginning in the humanities at Oxford and expanding out to other departments and countries—and continents!—I’ve tried and tested and adjusted a set of methods that now appear to reliably help many individuals write more, better, and more happily. The working hypothesis, which gathers more support every year, is that most problems with writing are in fact problems with creating conducive conditions for writing. The current sticking point might seem to be not knowing enough about the topic or about how to write a paper/essay/dissertation, or not having the capacity to synthesise so many complicated arguments or findings, but what most of this usually means is: I don’t know how to make dependable, calm, uninterrupted time in my week to work my way through these resolvable difficulties.

And how does one learn to make dependable, calm, uninterrupted time in one’s week for doing important but perhaps not terribly appealing things like working through writerly difficulties? Well, along with expecting it to happen by magic, another thing that doesn’t tend to work in more than the very short term is attending a time-management workshop that tells you to plan out your entire week in 30-minute segments, or deciding that because all productive people get up early you must set your alarm for 5:30am and then not leave your desk until the damn thing is finished. Neither following someone else’s rules nor forcing one’s way through with willpower ever works for long.

What works is, at its simplest, making writing feel as nice as possible. And the way to achieve this is always a mixture of deeply predictable and highly specific. The predictables include:

knowing what you’re doing at a high level (e.g. what this project is for);

knowing what you’re doing at a low level (e.g. what the next half-hour is for);

getting the bodily foundations (food/drink, sleep, movement, state of nervous-system arousal) as good as they can be;

working with your natural rhythms of energy and focus;

getting other people usefully involved (or helpfully absent);

and having a strategy for preventing and dealing with interruptions (especially the tech kind).

The specifics mean: everything that for a given individual is entailed by each of these category headers.

Thanks to this reliable pattern of structural similarities laid over with implementational variations, there’s a lot that we can do in the classroom setting to allow every individual to both appreciate the power of the general principles and start to discover what their own personal preferences are. Getting a chance to do this matters for everyone, and it matters especially for those whose lives outside the classroom are or have been shaped significantly by instability, fear, or suffering, because these mean that their defaults are likely to have come further adrift from stably effective routines. This in turn means that the creation of such routines may be more difficult, but that the resulting transformation may be all the more profound.

Summer writing bootcamp for the Baillie Gifford Writing Partnerships Programme, Humanities Division, University of Oxford, June 2019

3 Getting specific about solutions

In the writing courses and workshops that I’ve evolved over the years (and continue to), the design choices are intended to strike a balance between giving participants a chance to experience any variation on the core principles and giving them the invitation to start exploring their own variations right from the outset. This two-pronged approach is intrinsically well suited to those experiencing or healing from trauma, because it gives a baseline of certainty overlaid with potential for individual experimentation; it creates a space for exercising personal agency, as well as clearly defined parameters in which to do so. Everything I’ll be describing can be adapted for classroom settings, so let me give some examples.

One factor I learnt early on to impose lack of choice about is tech connectivity. Most of us have an addictive relationship with email and/or our phones, and this means that we find it hard to choose to be without them, and that we may experience salient (positive and/or negative) effects when we find ourselves “forced” to be without them. Experiments with rules around phone and other device use are becoming more widespread in educational settings, and these are usually imposed on students in a top-down fashion. The same is true of the courses and workshops I run—with the crucial difference that individuals choose to participate knowing that this will be a condition of doing so. This creates an interesting two-layered state in which everyone has chosen to relinquish the choice to check their email, their messages, their preferred social-media account and news site, etc. Not many people tend to report choosing to do this as a regular habit prior to our workshops; some report starting to do so as a result; and most come with a sense that their phone, media, news, and/or email use is in some way detrimental to their work and/or their wellbeing, meaning that they’re motivated to try something new.

In these workshops and in the classroom setting, the fact of having chosen not to have a choice can be powerful. If everyone is there voluntarily, having known in advance what the rules are, then their presence, with the intention of obeying those rules, is a support to everyone else who is intending to do the same. If everyone knows that every student in the class chose the class knowing that everyone’s phone (including the instructor’s) would be relinquished at the start, this makes a difference to how that rule can be “enforced”. In person, the rule can be implemented in a way that gently and humorously conveys “this is not optional”: I’ve long made use of a large colourful cake tin that I take round the room like a collection plate, requesting that everyone deposit their phone into it, ceremoniously closing it once full of phones, and leaving it somewhere visible to signal our shared commitment. Online, the onus shifts more towards self-directed resistance: I give suggestions for how to make one’s phone as inert as possible and how to place it out of reach and/or sight, make visible my own version of doing so, and convey that I trust everyone to do so—and that I’ll probably never know if they don’t!

A shared commitment to being right here, right now is one example of conducive conditions for writing that individuals can thus experience a generic version of: They have a small amount of choice about implementation in the online setting, but this is essentially a case of “experiencing any version of being tech-distraction-free is a win”. Then there are the aspects in which I give participants more significant latitude in how to instantiate a principle.

Completed writing workshop planning/tracking diary, summer 2024

Goal-setting for our timed writing sessions is an example of where participants are encouraged to work the details out for themselves. I’ll typically begin by asking whether anyone makes a frequent habit of setting goals for working sessions, and what their reasons are if so, to lead into discussion of its potential value: for example, as a way of clarifying one’s intentions in advance for a specific amount of time, as a way of learning how much one is capable of in a given time, as a way to motivate oneself to achieve something specific and congratulate oneself for having done so. I typically suggest that participants be both highly precise and more modest than they might default to, but I emphasise that in other ways this is absolutely their choice, informed by what they know about their project, what they intuit about their energy levels and inclinations right now, and so on. Once they’ve articulated a session goal, I typically ask them to rate their confidence (from 0 to 10) about completing the described goal in the available time, and I invite them to adjust the ambition level if their rating is lower than a 7. In small ways like this, individuals learn to direct their attention towards aspects of their working experiences and processes that are often ignored, and to get curious about the difference that small differences can make. And the ringing of a pretty brass bell at the beginning and end of the timed sessions makes the Pavlovian aspects gently explicit!

Trusty brass bell for timekeeping and cake tin for phone removal

Agency and learning play out in interesting ways from such innocuously prosaic starting points. Lifting the burden of choice creates striking effects: A higher-level choice to relinquish in-the-moment choices and delegate them to someone else (the facilitator/instructor) frees up cognitive-emotional energy for those interesting writing-specific difficulties—something especially valuable when those resources are already depleted by the processing of trauma. And attending to minutiae opens up space for self-knowledge: Performing mini experiments with goal-setting and other details during our time together is a natural way into the invitation to set a “what, when, how long, how” plan for tomorrow, or to design a fuller writing-centric behavioural experiment with careful design, predictions, review date, and learning prompts. Learning to take an experimental attitude to one’s own life can have profound benefits to our capacities to appreciate what’s working, spot promptly what isn’t, and shift rapidly from identifying problems to trying out solutions. The meta-habit of paying curious attention to our habits is valuable for everyone, and it’s more important (and also easier not to develop) the more difficult life currently happens to be.

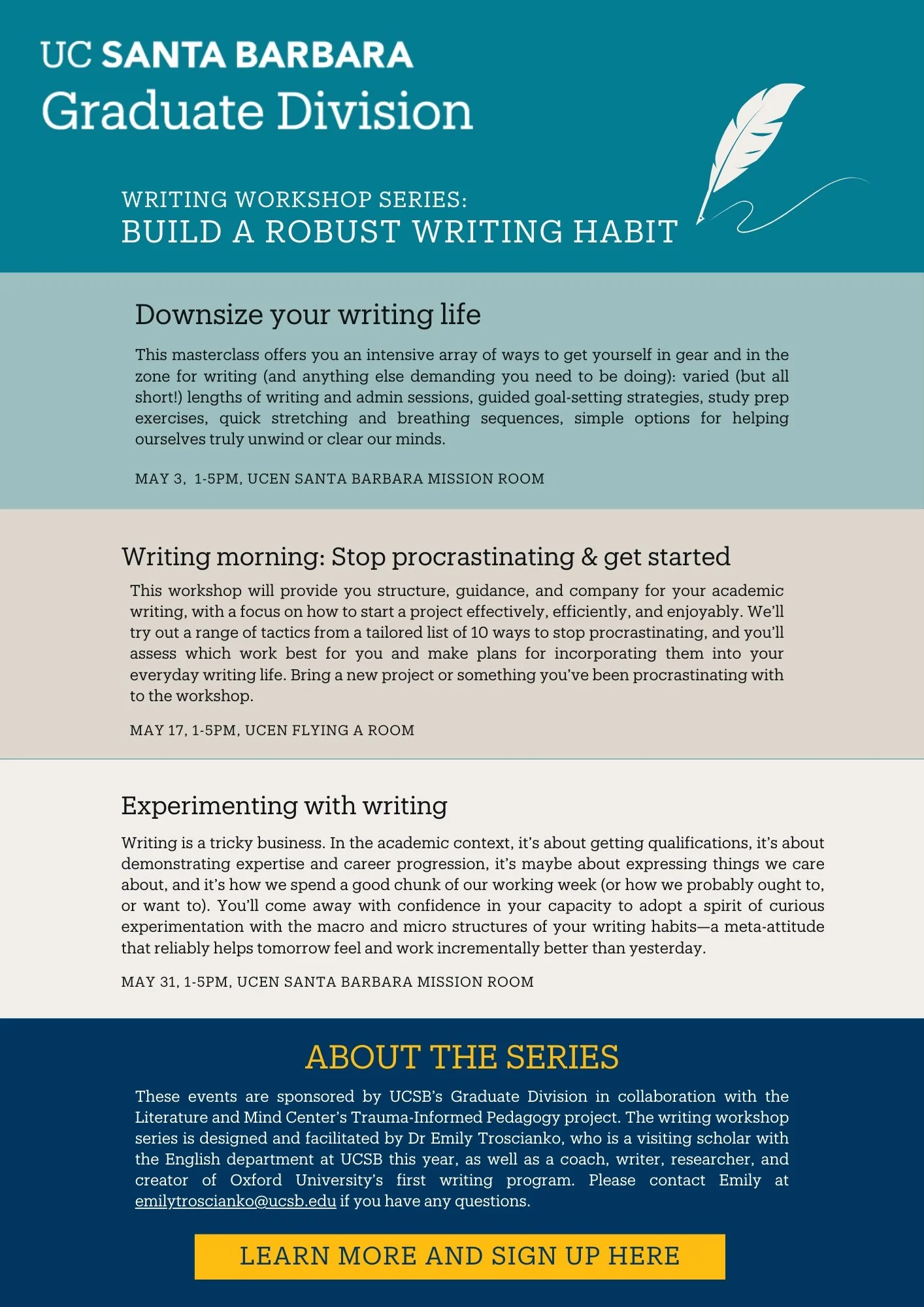

4 Evidence from graduate students at UCSB

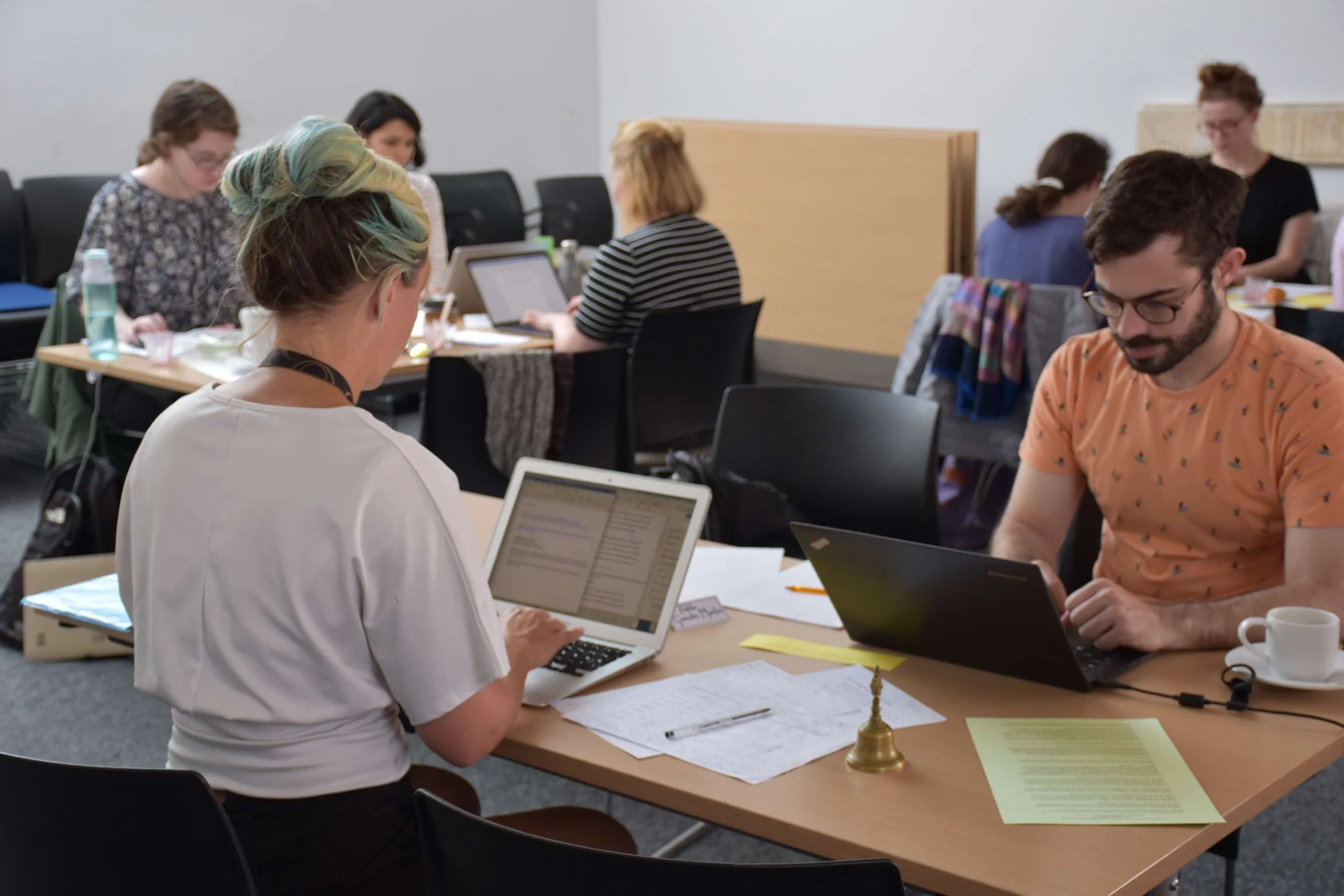

To flesh out the ideas I’ve just introduced, I’d like to give a flavour of the priorities, preferences, and insights expressed by participants in a workshop series I ran for graduate students at UCSB. They exemplify the benefits that can flow from an experience-informed approach to writing support. On Friday afternoons in May 2024, I ran three half-day writing workshops: 1) “Stop procrastinating and get started” (attended by 15 participants); 2) “Experimenting with writing” (15 participants), and 3) “Downsize your writing life” (14 participants). Students came from a wide range of departments and PhD stages, but they skewed towards humanities and social sciences and were mostly in their 2nd to 6th year. With the exception of two individuals in workshop 2, all participants were women. They brought mostly dissertation chapter or prospectus works-in-progress, but also conference and journal papers, term papers, and other projects.

UCSB writing workshop series flyer, spring 2024

Asked in the online survey, “What are your primary writing-related challenges or problems right now—what would you most like to get rid of when it comes to your writing?”, responses included strongly negative emotional factors such as fear, anxiety, avoidance, perfectionism, feeling daunted, and lack of confidence. Problems with procrastination and finding time to write accompanied these difficult emotions. We may infer that the causal relationships flow in both directions here: from finding writing emotionally difficult to not making time for it, and from failing to make time for it to generating avoidant patterns that make it more emotionally difficult.

Asked to turn to the positive, with the question “What are your primary writing-related aspirations right now—what would you most love to bring into your writing life?”, respondents described aspiring to a regular writing routine, schedule, or habit that brings with it pleasure, fun, curiosity, and confidence in both drafting and editing. To some, the very idea of such a routine seemed mysterious or intriguing. Evocations of a desire to build rhythm and flow were striking. And asked what helps most with their writing—that is, what feels conducive to getting closer to this aspiration—it was striking that most individuals did already know what helps; only a few said that they had no idea. This suggests that insight is not the problem; practical follow-through is. In the shift from what the Relations essay by Julie Carlson presents as the bad (fearful) versus good (eager) versions of “anxious to write”, a prevalent theme in responses was—fittingly, given Julie’s interest in friendship as a crucial channel for anti-managerial academia—the helpfulness of other people, including for direct feedback on writing, for discussing writing, for accountability, and for simple co-presence or body doubling. Some responses mentioned mind/body factors such as movement and being well rested and well fed. Other common factors were the importance of a comfortable (quiet, undistracting) environment to work in plus the value of knowing what one is doing, including having a routine and especially breaking down large tasks into smaller ones.

Creative workshop catering

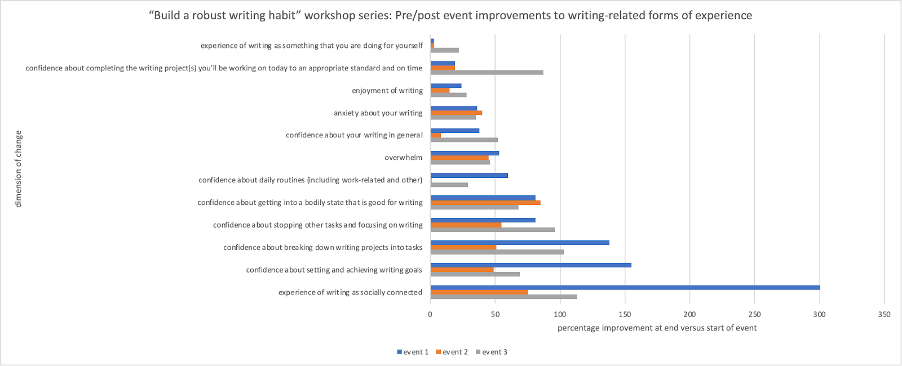

Turning to the effects of the workshops specifically, we gathered quantitative data about the benefits of taking part and the strategies perceived to be most helpful.

In one set of questions, participants rated their current state at the start of the workshop and at the end, on a range of dimensions relevant to confidence and positive experiences with writing. In this series (shown in the chart below), for all 12 dimensions and across all three events, the average change was positive, with percentage improvements ranging from 1% (for confidence in daily routines, after event 2) to 300% (for experiencing writing as a socially connected activity, after event 1). Goal formulation and achievement of goals showed substantial improvement, as did confidence in ability to focus on writing and get into a good physical state for it.

Improvements in current state by dimension and by workshop

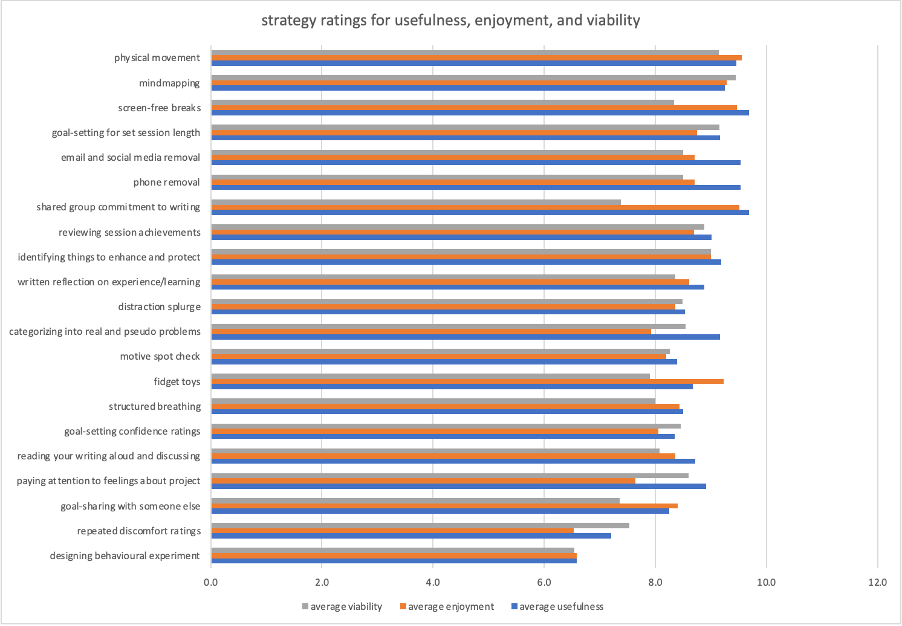

The other major multiple-choice question sequence inquired into the specific methods that participants considered to be most valuable to them. These methods can be hypothesised to contribute to the mechanisms by which the documented improvements occurred. Here we found that all the major strategies introduced during the workshops were perceived by participants to have significant value for them, where “value” is denoted by the total scores for participants’ ratings of each strategy’s 1) usefulness, 2) enjoyment, and 3) viability for their lives beyond the workshops. The average total value ratings across participants and events ranged between 20 and 27.9 out of a possible 30.

Mindmapping for a journal article, starting with a question (“How & why is agency important in eating disorder recovery?”)

Physical movement and screen-free breaks (i.e., simple bodily contrasts to “sitting at laptop” mode) were rated particularly highly, along with mindmapping (an exploratory, nonlinear tool for preparing to write). The next highest-rated set of strategies concerned intentional goal-setting and removal of distractions. Overall, these results suggest that (as Sowon Park also argues in her essay on Bodies) the common neglect of bodily aspects of academic activity needs correcting, and that other pragmatics—simple methods for cognitive “warm-up” and the details of goal-setting and distraction removal—make major differences too. Aili Pettersson Peeker’s exploration, in her practically oriented essay on Teaching, of the value of fidget toys is another beautifully specific example here!

Asking how the three dimensions of usefulness, enjoyment, and viability break down for each strategy, we find (as shown in the figure below) that there are no major incompatibilities amongst the three. The absence of sizeable differences amongst these ratings indicates that there are no major conflicts between what individuals find useful, how much enjoyment they find in these things, and how viable it seems to incorporate them into their everyday lives. This is a striking finding given the extent to which feelings of dread, anxiety, and overwhelm around writing were manifest in participants’ pre-workshop ratings and free-response testimony. Methods that work to disrupt these distressing and inefficient dynamics also feel good and are feasible!

Usefulness, enjoyment, and viability of writing workshop strategies averaged across participants and events

Overall, we can conclude that these practice- and body-oriented methods, developed primarily in the UK academic system, seem to work well at UCSB. There appears to be a need and desire in at least the graduate student population for approaches that take the psychological aspects of writing seriously, and that address them specifically through a habit-focused lens. The hypothesis I formulated in my work with UK and European students and researchers—that most writing problems are in fact problems with creating the conducive conditions in which to write—seems borne out by the data gathered here. And a couple of enjoyable guest sessions with Julie’s undergrad class “Trauma-informed literature and classrooms” reinforce this impression for the undergraduate level too.

5 The upshots for the classroom

What does this mean for the classroom? My learning from running workshops and courses at UCSB and beyond suggests that a lot can change when one makes time for experience and process, rather than demoting them radically below content. Making such a shift in ratios—even only upping experience and process elements from 1% to 10% of class time, for example—involves a corresponding shift in the balance of information-giving versus coaching elements. Good teaching always involves both: imparting knowledge, or making knowledge accessible, to others to help them learn about a subject; and helping others to learn about themselves and to put this self-oriented learning into action. This second form of learning is obviously precious in the growth of the individual towards wisdom and compassion. Crucially (as Sowon’s trauma-focused Bodies essay sets out so clearly), it is also indispensable to any meaningful acquisition and application of subject-specific knowledge, however apparently transactional.

Summer writing bootcamp, 2019

How might this type of shift, incorporating more process- and experience-oriented elements into a coaching-informed style of teaching, play out in practical terms? Here are some ideas to consider:

Including process-related factors in class descriptions (e.g. indicating policies on phones, breaks, and other aspects of participation)

Framing in-class activities through an experimental lens (e.g. inviting students to take a few minutes to map out an approach to a task before diving in)

Including experience and process in the framing of homework assignments (e.g. asking students to report on their methods as well as their outcomes)

Replacing advice-giving with question-asking as often as possible, both 1-1 and with the whole group

Foregrounding processual and experiential factors in what one conveys about one’s own learning and writing processes, to model this approach as self-evidently valuable

Many of the suggestions made in the Teaching essay’s overview of practices to consider adopting or adapting fall under the same umbrella. And you may come up with all kinds of specifics that feel like a good fit for you and your students to enjoy bringing process and experience centre-stage. (I should note that I would encourage you to consider how you could adapt them for graduate student advising as much as for undergraduate teaching.)

It’s also worth noting that many of these practicalities are intrinsically suited to the internet era, for both digital natives and digital immigrants. They’re a meaningful response to the fact that information is not what students need from professors anymore: They are already drowning in information, and what they need is help navigating it. Of course, in the era of artificial intelligence that is now unfolding, help with the navigation is offered by AI too. What does this mean for experience-informed writing? Well, working with this paradigm makes clear that there’s no point in getting AI to generate the entire product for you, because that short-circuits the processes and experiences that are most of the point when mere information comes cheap. As for more nuanced uses of AI as a writing aid, using AI may, for some individuals and in some contexts, increase their ability to function despite trauma (for example, by helping give the blank page some preliminary contents), and for other individuals and contexts it may reduce this capacity (for instance, by fuelling feelings of personal inadequacy or impotence). My sense is that the more we embrace the practicalities of learning about ourselves through writing and writing via ourselves, the better placed we are to incorporate AI constructively into the processes of design and discovery that apply recursively to our writing and our lives. If you know at what points in the drafting and editing process you could most do with input, and if you know how to test the results of this input against your writerly instincts and your intentions for this particular piece, then you are likely to be able to develop a form of AI-assisted writing that enhances process and output rather than creating overdependency or impairing individuality. Writing has always been one of humankind’s most powerful tools for thinking, and one of our jobs as teachers of writing is now to help students harness the complex cognitive feedback loops that circle out through the material and digital environment to the benefit rather than the detriment of the similarly complex dynamics that create and sustain trauma and healing.

End of an outdoor stretching break, summer writing bootcamp, 2019

Overall, then, I suggest that attending to process and experience when we teach helps students develop and apply their understanding of themselves to their academic work and life. I see the methods and principles involved in doing so as part of what trauma-informed pedagogy needs to succeed in its intentions to improve students’ experiences and outcomes at university. These methods and principles are one possible response to the Relations essay’s call for a profound openness to letting our pedagogical practices evolve—as we ourselves do, and as the world does. And they are also, by definition, enjoyable to implement. I hope you’ll have fun devising your own variations on experience-informed.

Helping hands to many words

(A meta-note on process: I drafted this at home in Goleta over five sessions in four days, four of them first thing in the morning after journaling and 10 minutes of HIIT and before looking at phone or email, all of them with tea. I wrote the first half without a plan, then sketched out some bullet points for the rest. I estimated 3 hours for a first draft good enough to share with my brochure coauthors because I thought I was going to draw heavily on a previously written report about the graduate workshops. It took me 4 hours 15 minutes (and then another 50 minutes for the first edit) because I wrote a lot more from scratch than I’d expected to—and because, as usual, I wrote more than I’d been asked to! Then, of course, the rest of the editing process took its time: Back in my boat home in Oxford, I spent 95 minutes one spring morning attempting to shorten it, enjoyed an 85-minute Zoom meeting with the rest of the team to discuss all our drafts, and spent another 95 minutes a little later into the spring—still with plenty of milky decaf tea to hand—incorporating the changes they’d suggested, and reading the whole thing aloud to improve the overall style.)

On our Conversation page you can find some questions that may help you reflect on your responses to these ideas and consider ways of experimenting with anything that seems interesting to you. Check out the questions here.