TEACHING

What I Don’t Know in the Classroom

BY AILI PETTERSSON PEEKER

aili@writing.ucsb.edu

Introduction

One of the problems with trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education is the question of practice. Guiding principles like safety, trust, and transparency all sound nice, but what exactly do they look like in the college classroom? In this essay, I discuss specific teaching practices that I have changed in my own teaching to try to make my classrooms more trauma-informed.

One way to think about these practices is as alternatives, or additions, to trigger warnings. As explained in the Bodies and Relations essays, we think that trigger warnings are not sufficient and rarely even efficient in supporting students who enter our classrooms with histories that include trauma. But even though trigger warnings are problematic, the issues that underlie the demand for trigger warnings are very real; our students often do enter our classes with heightened anxiety, there is an increased presence of trauma in the classroom, and few teachers know how to address—let alone “solve”—these issues. My goal in discussing some concrete practices is to provide practical pedagogical tools that do not minimize either the seriousness of student trauma or the complexities and ambiguities of textual material and humanities training.

The practices discussed here are presented with the aim of adding specificity to the breadth that characterizes much of the existing material on trauma-informed pedagogy (the majority of which is tailored to K-8 education). They provide a range of methods that take our students’ diverse backgrounds and realities into consideration.

The idea is not that a teacher has to do all the things listed in order to earn an official stamp of being trauma-informed. Rather, my aim is to provide resources for and reflections on teaching in an ever-changing reality that is characterized by fundamental uncertainties. Uncertainty is an aspect of life that it is particularly difficult for traumatized individuals to adjust to, and one that has specific effects on a person’s capacity to learn. As Julie Carlson writes in the Relations essay, “Ignoring the effects of trauma on the capacity to learn does not make them disappear.” By offering resources for addressing these effects, I hope to provide something that can make it a little less stressful for university teachers—particularly new ones—to craft a learning climate that is characterized not by avoidance, mistrust, and fear but by curiosity, openness, and experimentation.

Before walking into the South Hall classroom to lead my first discussion section as a Teaching Assistant in the English Department at UCSB, my attitude was definitely characterized by both fear and avoidance, and probably by a fair dose of mistrust too. There were the classic imposter syndrome worries alongside my deep-seated fear about how on earth I was supposed to fill fifty whole minutes with discussion. What if no one said anything at all? (Being from the culturally taciturn Sweden, this fear is not completely irrational.) In addition to these fears, there were also worries that I now recognize as connected to trauma-informed questions, even though that is not the language I would have used at the time. I worried about discussing the topics of the literature we read in the right way, or at least in a not-bad—not offensive or re-traumatizing— way. Since we read texts like Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, Hamlet, and a collection of poetry about global military operations, a range of difficult or “sensitive” topics were bound to arise in class discussions. What if I said the wrong thing, or planned an activity that opened up a can of derailed discussion worms where students shared offensive takes on the texts? What if I messed up in one of the very many other ways in which I could imagine messing up?

Much of this fear was rooted in inexperience. When I came to UCSB to begin my PhD in 2017, I had never taught at a university before. I was only briefly familiar with the US college experience through a semester abroad in North Carolina. As a student, I had never had a Teaching Assistant or been to a discussion section. My only teaching experience was a brief side gig teaching Swedish as a foreign language to a small group of adults who had just immigrated to Sweden. Those adults seemed decidedly different from the mostly young faces staring at me from their uncomfortable seats in the South Hall classroom, and the exercises in Swedish verb conjugations and polite everyday expressions seemed politically and emotionally very safe compared to the texts on our syllabus.

One thing that I was not worried about that first day but that I soon became worried about is what I should do when a student disclosed that something traumatic had happened to them. As a Teaching Assistant in a humanities course, I quickly realized that both the traditional essay and more creative options often invited students—often implicitly but sometimes explicitly—to reflect upon their own relationship to trauma. What this meant was that students often disclosed traumatic personal experiences to their Teaching Assistant, whose role as (most often) less authoritative and closer in age and experience to the students than the professor can invite even more disclosures than the average tenured humanities teacher will get. As a new teacher, my instinct was often to attempt to fix whatever issue the student was dealing with. In this way, my initial reaction exposed one of the most common misconceptions about trauma-informed teaching: that it turns teachers into therapists. Realizing that trauma-informed teaching means striving to serve students with histories of trauma rather than attempting to treat them is one of the most fundamental and helpful facts that this approach has helped me understand.

The limits of what I can do for a student in distress are something I still have to remind myself of when a student decides to share something traumatic in writing or in person, but learning and remembering my limitations as a teacher has been key for me as I learn about trauma-informed pedagogy. Before, I would feel woefully inept and inadequate at handling a situation whenever a student would tell me about something traumatizing they had experienced or were living through. Now, with a more robust sense of what my role is as a teacher, I don’t feel quite so bad. I know what I can do and what I can’t do, which many times is just as important.

*

Today, I am not quite as fearful when I walk into the classroom on the first day of the quarter. I still worry about doing or saying the wrong thing, and I often think that there is no way I will manage to fill whatever time slot I have with material when I sit down to craft a lesson plan (even though I almost always end up realizing that I will not have time to get through everything I planned—Swedish fears die hard). In the coming sections, I discuss some of the practices connected to trauma-informed approaches that I have changed about my teaching and how this all connects to empathy, which happens to be what I wrote my dissertation about.

Isn’t this all just more work?

Before getting to the specifics, there is one looming question to address: Isn’t trauma-informed pedagogy just one more thing that you have to do? Rethinking your courses and your teaching through a trauma-informed lens can feel like more work—an additional demand in the never-ending rain of demands infringing on your already overcrowded schedule. And sometimes it is. Trauma-informed pedagogy requires foreseeing things and thinking through your course structure in a way that you perhaps had not done before. It is work, it takes time, and it should be compensated. That last part does not always materialize, of course. Trauma-informed work at the US university today is typically both invisibilized and feminized, and the labor often falls on faculty members who represent intersectionally diverse identities in terms of race, gender, class, ability, and sexuality, adding to their already disproportionately overfull plates. I have no intention of pretending that trauma-informed work does not require labor or time; my hope in articulating practices and sharing reflections on my own teaching is to make visible and contextualized the kind of labor that teaching today asks us to provide.

The way I see it, one of the major teacherly benefits of trauma-informed pedagogy is that it can be a way of minimizing the risk of traumatizing teaching experiences. Even though I could not articulate it at the time, a sudden blow-up or other erosions of student trust were what I feared when walking into the classroom. We have all heard about these experiences (or lived through them first-hand) that sometimes provoke career changes and always end up causing permanent confidence scarring. Trauma-informed pedagogy is not, of course, a guarantee against these experiences, but it can help reduce the risk of them. By reducing this risk, trauma-informed pedagogy can make it easier to approach teaching in a mode of creative and joyful experimentation rather than with fearful risk-avoidance.

Sometimes—at least in my experience, and I will discuss this in more detail below—trauma-informed restructurings actually do end up saving you time as an instructor. This is perhaps most clearly the case when it comes to policies regarding accommodations. Taking trauma-informed approaches seriously asks us to create structures that make it easier for students to feel in control of their own education, to figure out what they need, and to communicate what they need to the right person. Providing clear guidelines for how students can ask for accommodations can save time (not to mention stress, for everyone involved) because, for one, providing clear guidelines about things like how students can make up for missed work decreases the likelihood of those last-minute requests for extensions and alternative assignments that have a tendency to snowball in your inbox right before the end of the quarter.

Providing clear but flexible guidelines is not the same as providing individually tailored accommodations. The latter is not feasible when you have 25-75 students per quarter, let alone when you teach a large lecture course (or even when you have “only” 15 students). Rather than requiring individual approaches, trauma-informed pedagogy offers methods to reconsider course structures in a way that builds in flexibility and clarifies options when students do need accommodations. Providing clear policies regarding accommodations is one way to acknowledge that students—like teachers—have complex lives that sometimes infringe on their role as students. To acknowledge this reality, it was necessary for me to unlearn certain ideas and assumptions: that suffering is necessary for learning, that a tradition or methodology or text is objectively valuable rather than subjectively important, that a student is a person with no obligations or commitments other than studying, or that “rigor” is an educational goal in and of itself. For students who have histories of trauma, speaking (up) and asking for accommodations may be more difficult—sometimes even unthinkable—than for students privileged enough to have a past that is (relatively) free from trauma. In this way, then, demystifying the process of asking for accommodations by spelling it out in, for example, the syllabus is one way of attempting to level the educational playing field.

Trauma-informed teaching and empathy: Or, what I don’t know in the classroom

This issue of who asks for accommodations and who does not is linked to the role of empathy in the classroom. This is something I think a lot about, partly because I happened to write my dissertation on the topic of empathy, power, and privilege but also because it exposes important questions about the power dynamics of the classroom that need to be taken into consideration when crafting a trauma-informed pedagogy. In the most basic sense, the connection between trauma-informed pedagogy and empathy is about how I, as a teacher, recognize and respond to others in the classroom, and it comes down to the never-ending task of reminding myself of what I don’t know about my students.

This task becomes particularly important when trauma enters the classroom. As Sowon Park writes in the Bodies essay, “When students are in states of hyperarousal (triggered, panicking, enraged) or hypoarousal (dissociated, shutdown, disengaged), their behavior can be misread as disinterest or defiance.” This misreading often comes with judging. I do this all the time. I judge students I (mis)read as disengaged, uninterested, defiant, or just plain rude. I have reactions and likes and dislikes. Quite often, however, it turns out that the student that I thought was just fundamentally uninterested in my course (the same course that I have spent so much time thinking about and designing in the—to me—most interesting way possible!) based on their facial expressions, their body language, or their lack of engagement in my ingeniously designed lesson plan is going through a Title IX process; or they are stuck in an abusive relationship; or they have just lost a loved one; or you-name-it. Sometimes, I do not find this out until later, when our campus CARE office contacts me with an official request for accommodations, or when the student decides to tell me what is going on in their life. Like every other teacher, I feel bad about my initial judgment when this happens; of course I want to trust my students, but situations like the ones I just described show how this trust can and often does break down.

As a new teacher, this trust was particularly tricky to offer because I tend(ed) to take any sign of disinterest as a sign of my incompetence or incapacity to keep students engaged. In other words, disinterested students would feel like a critique, perhaps even an attack. Since being a new teacher often comes with having a rather fragile confidence in the classroom, the response to a critique or an attack often comes in the form of defense, and a really good way of defending oneself is to first of all decide that the problem is not mine, but someone else’s. This defensive response also tends to shut down any attempt to entertain possibilities of what may actually be going on in a student’s life. Reminding myself of the myriad possible explanations for a student showing signs of being uninterested or defiant when this happens is, to me, the hard but crucial work of staying trauma-informed in the classroom.

Just as we can never guess what is triggering to a certain student (see both the Bodies and Relations essays), we can never guess what is going on in a student’s life. Who discloses what to a teacher—who is ultimately a figure of authority—is highly structured by privilege and personality, among many other things. Do you come from a family where people told you that it is OK to ask for accommodations in college? Did you grow up with discussions about university life around the dinner table at all? Is it easy or hard for you to open up to others? To authority figures? Because I can never answer these questions from my vantage point as a teacher, I have to operate on a level of trust that requires me to recognize all the things I cannot know about each student. More than this: I have to be comfortable with what I do not know, and I have to design policies and practices based on this—based on the premise that I cannot, will not, and probably should not know what, exactly, is going on in my students’ lives that may cause them to need an extension or behave a certain way in the classroom. These policies should not depend on students disclosing personal information or revealing traumatic pasts, both because that is not a particularly dignified way to structure an education but also because my reactions to such disclosures will always be formed by my own inescapably limited and narrow perspective. Is the situation one I can relate to? Is the student a type I can relate to? These two questions about my initial reactions connect to larger questions about systemic injustices in higher education: Why are certain students and their suffering easier to understand? Why are certain students and their suffering invisibilized, to me and to the institution? The reality of disenfranchised trauma (for more on this, see the Bodies essay) as well as our students’ lived wisdom regarding this issue tell us that these questions are crucial for trauma-informed work to be effective as well as equitable. Recognizing the multiple, complex, and intersectional power dynamics that structure my own answers to these unanswerable questions reminds me of the importance of acknowledging how much I don’t know about my students.

How I empathize with my students will always be structured by cultural, socioeconomic, racial, and other perceived differences that complicate this form of human knowing. Constantly reminding myself of these complications and of the limits of my imagination—of my ignorance—helps me to proceed with caution when it comes to imagining students’ lives. This caution can help me avoid jumping to conclusions that inevitably will influence how I relate to students, especially in times of distress. By respecting the unknowability of my students, I can identify and honor this ignorance as a way of respecting my students as well as their right to privacy, and as a method for ensuring that I minimize the risk of treating students differently based on my empathetic blind spots.

What can trauma-informed teaching look like in the classroom?

There is no single definition of what constitutes trauma-informed educational practice. What works well in one situation and for one person may not be right for someone or somewhere else. In the following section, I share examples of classroom practices both big and small that I have experimented with that can indicate to students that the course has been crafted with them—as whole persons rather than disembodied consumers of education—in mind. The practices that follow represent suggestive rather than prescriptive or exhaustive recommendations. None of them are revolutionary, but they are concrete and—I hope—practical. The practices are almost exclusively things that I have changed since I was a very new teacher, and many of the practices keep changing as I learn more about teaching. Collectively, these practices aim to acknowledge the fact that the states of students’ minds and bodies affect (for example) their attentiveness and willingness to take risks, and that their individual histories of textual literacy, familiarity with trauma and adversity, and senses of being welcome in higher education enter into educational spaces with them.

Many of the following practices are inspired by a wide range of people and resources on our campus. In my case, the ONDAS/CITRAL Seminar on Equitable and Inclusive Teaching and Learning has been very helpful for thinking through trauma-informed teaching practices while benefiting from ideas and expertise shared by teachers with similar interests and worries. The practices below should all be considered in parallel and in combination with resources such as CITRAL’s resource library, the several guides and workshops offered by the Office of Teaching and Learning (particularly the Classroom assessment instruction), the Red Folder from CAPS, and CARE’s resources for survivors as well as people interested in prevention education. We are also lucky to have spaces like the Gevirtz School of Education, the Hosford Clinic, and The Healing Space/Kindred Collective for Healing and Liberatory Traditions on our campus. All of these organizations, collectives, and people host workshops and produce research connected to trauma-informed pedagogy.

Similar to Emily Troscianko’s insistence on how creating a well-functioning structure for writing requires a combination of predictability and individual modification, the practices I discuss below help me craft courses with enough predictability to enable students to feel guided while leaving room to figure out what works for them as individuals. As Emily suggests in the Writing essay, “This two-pronged approach is intrinsically well suited to those experiencing or healing from trauma, because it gives a baseline of certainty overlaid with potential for individual experimentation; it creates a space for exercising personal agency, as well as clearly defined parameters in which to do so.”

The syllabus

I try to write my syllabi in language that is as straightforward as possible and I try my best to envision it as a document that both describes the course content and addresses the course participants as people. This sounds straightforward, but specifically for new and perhaps insecure teachers who are constantly told that the syllabus is a “contract” and that it must include a whole range of things, it is not. For me, what those aims mean in practical terms is that I try to use “I’s” and “you’s” rather than “the instructor” and “students” (for example, changing from “after completing this course, students will be able to…” to “when you have completed this course, you will be able to…”). This grammatical move away from bureaucratic anonymity is one small way in which I hope to signal that the course is crafted with actual people rather than anonymized consumers of knowledge in mind.

And yes, I am aware that many—perhaps even most—students do not read my syllabus, no matter how hard I try to make it inviting and no matter how many times I say that it is really important that they read it. To make sure that as many students as possible read as much of the syllabus as possible, I have recently started incorporating in-class assignments (often about some exciting grammatical concept such as the use of active and passive voice) where the text we are working with is our syllabus. This does not get every student to read the syllabus in its entirety, but it can, I hope, lead to more informed students (and fewer emails with questions about things they would find information about in the syllabus, thus getting rid of a particularly annoying hindrance to empathy for teachers: when students email to ask a question about something written on the first page of the syllabus you have spent so long perfecting).

Making students read the syllabus as part of an in-class activity has the added bonus of increasing the likelihood of them actually noticing the extensive list of campus resources we all include in our syllabi. Pointing all students toward campus resources including food security and basic needs programs, mental health services, emergency financial aid, health and wellness, non-traditional (aka new traditional) student resource centers, as well as tutoring and academic support can be a way of encouraging them to think of these resources as aids to performing well in the class rather than places to turn to if you are not smart, rich, normative, or healthy enough to be a college student.

First day of class

There are many things I worry about doing and not doing during the first encounter with students at the start of any given quarter. One small thing that I have found has helped me build a relationship based on trust and respect in the classroom is a particular way of identifying and learning names and pronouns when I teach small-ish classes. In addition to the usual introductions that ask students to share their names and pronouns verbally, I ask students to write down how they pronounce their names[1] on a first-day questionnaire where I’ve already written that my name is Aili, pronounced eye-lee. This simple activity means that I don’t have to guess or mispronounce (as frequently) and has the added bonus of saving time as I learn students’ names with these questionnaires as a study aid.

Attendance

My aim with attendance policies is one of the things that has changed most drastically in the eight years since I started teaching. I used to craft a pretty rigid attendance policy for my syllabi, based on some ill-defined notion that it was better to spell out a strict policy and then make exceptions than the other way around. (I vaguely remember this approach being recommended to me as a way of establishing authority in the classroom as a new and fairly young TA who also happened to be a woman and an international student.) Although strict on paper, I rarely managed to be strict in reality and my policies today reflect this more dynamic (and realistic) approach.

Aiming for clarity and flexibility in policies about attendance, I try to communicate—in my syllabus and in the first week of classes—that I know that students are people with complicated lives and that my main role is to facilitate their lives as students. One specific strategy that has worked well for me is to have an “X absences, no questions asked” policy. I like this policy for three reasons: 1) It reinforces the idea that students do not have to disclose personal information when asking for accommodations; 2) It saves me the time of responding to pleading emails and crafting individual plans for multiple students; and 3) In avoiding this scenario, I minimize the risk of making an arbitrary judgment about what student and circumstance “deserves” to be granted what number of absences—a decision that will always me marred both by my limited knowledge of their situation and my (more or less conscious) judgement of the student asking for an exception.

Flexible deadlines

Allowing students to turn in projects (or a specific proportion of assignments) X days late, no questions asked, is a way to take students’ lives outside the classroom seriously. As a policy, it can alleviate anxiety about having to provide personal and often sensitive information to a teacher in order to “earn” an extension. The policy also minimizes those more or less frantic last-minute emails about accommodations and extensions. As teachers, we of course have grade submission deadlines imposed by the university and busy lives of our own, meaning that there are limits to how flexible we can be. In my experience, however, the vast majority of students do submit their work on time even with this policy.

Exit strategies

I have recently started to specify exit strategies related to physical, emotional, and mental safety in the classroom. What I mean by this is quite concrete: Literally and figuratively, where is the door if a student feels threatened? Students may want to physically leave the classroom for any number of reasons. Because leaving the classroom can draw an uncomfortable amount of attention to a student, I have started telling students that they can leave anytime to go to the bathroom (this always appears to come as a surprise for a fairly large number of students fresh out of high school) and that if they do leave the classroom, everyone else will just think they need to pee.[2] My hope here is that articulating this option can de-dramatize the act of taking care of your well-being while making clear that students are never trapped in the classroom.

Office hours

Another recent change in my policy-related practices is to designate “office hours” in a less impersonal or off-putting way. I have started calling them “student drop-in hours aka office hours” and have found it helpful to emphasize that students don not have to have a fully-fledged research idea or specific, prepared, and clever question to come by my office. This may seem like a silly semantic move, but many students worry about wasting their professor’s time if they do not have something important to say in the formal-sounding office hours visit. Some think that they need to make an appointment because of the emphasis on office hour. Minimizing the obstacles for students unfamiliar with university language can be one way of making more people feel entitled to make use of the resources they are already paying for with their tuition.

Group and peer work

As someone who (almost) always abhorred group work in school, incorporating group and peer work into my lesson plans is not intuitive. Since recognizing how these forms of participation can reduce competition and individualism, and since realizing how different kinds of students really appreciate and benefit from it, I now try to incorporate different forms of peer teaching, small group work, and group presentations into my classes. For example, I ask my Science Writing students to prepare and give group presentations in groups that I have designated based on their major, and I often use the classic “think-pair-share” method to start class discussion. These methods can help cultivate a classroom environment where students perceive each other as resources for working through difficult texts or topics together. (Yes, I know that this is easier said than done.)

Variations

Varying the modes and media of instruction is one of those pedagogical platitudes that to me always seemed too obvious to deserve time thinking that much about but that in practice has turned out to be more difficult than I thought. In the ONDAS/CITRAL Seminar on Equitable and Inclusive Teaching and Learning that I recently participated in, we were encouraged to keep a question in mind when crafting lesson plans: “what kind of student gets left out of this exercise?” and to then make sure that it is not always the same kind of student (e.g., introverts) who are being left out. To me, this simple question was somewhat of an epiphany because of how it exposed my own tendency to plan classes that I would like to attend as a student. Asking this question helped me realize and repeatedly remember that my students are different from me; that they may not enjoy or learn well from lectures, that they may in fact appreciate group work and class discussion. Asking this question also helps me remember that people teaching at universities are anomalies, given that we have chosen to spend 20+ years of our lives in educational institutions. Reminding myself that I am not teaching myself is one way in which I can minimize the risk of using myself as a blueprint when I make assumptions about my students.

With this mindset, it has become easier to present content in varying media (e.g., podcasts, video, music) and to create variation in classroom routines (e.g., via physical movement, paired work and group work, outdoor breaks), even when those modes and practices are ones that would have made my student self (or indeed my current self) cringe. Building in this kind of flexibility has widened how I understand participation by incorporating ways to “reward” active listening (e.g., via journaling, blog posts, questions submitted ahead of class), not just frequent speaking in class. This shift is significant from a trauma-informed perspective because listening is a crucial and culturally-variable skill that is overlooked when “participation” is equated with “speaking,” and because traumatic pasts may make it more difficult for certain students to speak in the classroom (more on this topic soon).

Grounding and orienting

There are many variations of grounding and orienting exercises but the version I have experimented looks like this: take three minutes to ask students to ground themselves by noticing where their bodies make contact with their chairs and the ground, then ask them to notice something in the classroom or outside the window that makes them feel calm, and then do a—don’t laugh—humming exercise together. This practice definitely did not come easy to me, and to be honest it is a practice that I have only used a handful of times. The first time I started class with a grounding and orienting exercise, I was probably more terrified than that first day as an instructor in a university classroom. I had 30+ years of built-up ideas about what should take place in a university classroom (not to mention a Swedish reluctance to do most things that seem too Californian or New Age-y), and collective humming was not part of those ideas. My personal fears aside, starting or interspersing class with a grounding and orienting exercise can support concentration and engagement, particularly when discussing potentially traumatic course material. Additionally, whenever I do take the time to do this, I have received overwhelming positive reactions from students who say that this practice calms and focuses them in a way that is hugely beneficial for class discussion.

Breaks

I used to see breaks as a waste of valuable class time, but research has begun to reveal the many benefits of breaks (among other things, breaks have been shown to improve college essentials such as reading comprehension and divergent thinking[3]). Reminding myself of this on a weekly basis when I am tempted to cram my lesson plans with information and exercises that feel absolutely crucial to the tasks at hand, I now do my best to include breaks in my classes. I try to encourage students to move and leave the classroom for a bit during the break, since both movement and a change of environment are beneficial for concentration, but this encouragement fails more often than not (the outside with all its possible awkward social interactions has a hard time competing with the allure of phones and laptops). Regardless of how they spend this time, giving students a break to attend to whatever might be on their minds—or to just not attend to anything in particular for a bit—may help them focus better the rest of the time.

Free-writes and small-group discussions

As someone for whom it takes a bit of time to gather and articulate thoughts, and whose first language is not English, discussion preparation in the form of free-writes and small group discussions is a practice that I actually have based on my own preferences. Before—or sometimes instead of—whole-class discussion, I give students time to write down their thoughts about a specific question, or a section from the class reading. This activity does not have to take more than a couple of minutes. I make it clear that no one has to submit this writing but that they will share their thoughts with other people. I also emphasize that the goal is to explore their own thinking rather than to write something “smart” or “good,” and that I encourage everyone to keep their hands or typing fingers moving for as much time as possible in an effort to discourage that academic malady called overthinking. On the best teaching days, this practice gives all students time to collect their thoughts, which in turn makes it easier to ensure that it is not always the fastest thinker and loudest speaker who speaks (over) others in the classroom.

This strategy can also help students engage with difficult material in a way that is manageable for them. It can help them feel more in control of their engagement with the material, which makes engaging with others about the material much easier. For students whose backgrounds might make it difficult for them to think clearly and quickly about a topic or idea or scene that may be upsetting to them, this practice can give them time to process their initial reactions and decide how and what they would like to share. For multilingual students who might need more time to formulate their contributions in English, it can ensure that they have a chance to voice their ideas at all. In these ways, this practice can be a way of making the classroom more equitable and accessible by making sure that it is not designed to always amplify the voices of those students who happen to be comfortable sharing their immediate thoughts on any given topic in front of a group of relative strangers.

Assessment

Most teachers I know hate grading. Grades are also, of course, a source of great anxiety for many students. Because of this, and because grading standards are culturally relative, it can be helpful to at least consider adopting a non-traditional approach to grading if you want to create a trauma-informed classroom. If you decide to implement any of these grading methods, often referred to as “labor-based grading” or “ungrading,” it is a good idea to offer students the option of traditional grading too, since the newness and flexibility built into these methods can be counterproductive in creating unnecessary anxiety for precisely the students you are trying to help. What I have found works the best so far in my teaching is the following practice, usually referred to as “specs grading.”

Specs grading (sometimes called “contract grading”)

I started using specs grading the first time I taught a course in academic writing at UCSB, partly because it was encouraged by my Writing Program mentors but also because it seemed to offer an opportunity for me to cut time spent on my least favorite job task. In specs grading (short for specifications grading), the teacher clearly outlines what work a student needs to do to earn a specific grade by creating ”grade bundles.” For example, the A grade bundle might require completion of all assignments, substantive revision of writing projects, office hours visit(s), and only a certain number of absences, while a B grade bundle requires less work and allows for more absences, and so on. This method gives students the option to choose what grade to work towards and clarifies expectations. Personally, this approach to grading student writing has freed up countless hours that I used to spend deciding whether an assignment had earned an A or an A- that I now can use to provide feedback on student work.

Giving feedback on writing that the students are then asked to revise is one way in which I try to invite dialogue throughout the writing process (rather than exclusively at the end of a project), a practice that I have found much easier to implement if there is no static letter grade stamped on the first page of a student’s first draft. An additional benefit of this approach is that it foregrounds the activity of writing over the final product of a text, so that the text becomes part of a larger act of self/other inquiry through writing. (See Emily Troscianko’s Writing essay for more detailed ideas on this topic.)

The vast majority of my students appreciate this grading system (if the course evaluations are to be believed), and they often point out how it enables them to take risks in their writing and promotes growth and learning. There are always, however, a couple of students every quarter who do not appreciate it (although I have never had a student opt out of this grading option). These students often express that the grading system is unclear and/or unfair in their final class evaluations. I have not managed to get specific enough feedback regarding this issue to know if these students would have had the same experience with a traditional grading system, but giving students the possibility to opt for a traditional grading system while doing my best to clarify my evaluation strategies (a never-ending task, it seems) is the best solution I have come up with so far

If you want to read more about specs grading or other forms of alternative grading systems, I recommend checking out this blog post from Duke’s Learning Innovation and Lifetime Education center. For anyone interested in the history of grades and how racist ideologies haunt current-day grading practices, Asao B. Inoue’s post on the topic provides a comprehensive overview on the history of grading in the US. The chapter “Teaching More by Grading Less (or Differently)” by Jeffrey Schinske and Kimberly Tanner, published in Life Sciences Education, historicizes the issue for teachers from all disciplines.

Creative options

Giving students the option of a creative final project instead of a traditional academic essay is my favorite way to make the grading part of teaching less grating. Whenever I do this, I add an “artist statement” to the assignment where students reflect on how their creative work and/or process connects to the course material. Creative projects have two added bonuses: it can energize students looking for creative outlets in college and the work turned in is most often an absolute joy to grade.

Grade appeal policy

If there is one thing that teachers dislike more than grading, it is probably complaints about grades from students who think that their performance in a class was unfairly assessed. As a strategy for minimizing the stress of dealing with upset students wanting to negotiate their grade, I have started to include a policy for grade appeals in my syllabi. I borrowed this strategy from Sowon Park after I TA:d for her and found that this clarity made my job as a Teaching Assistant much less stressful. This policy includes a specific time frame within which a student can submit a grade appeal (e.g., no sooner than 24 hours after the assignment is returned—this is the “cool off period”—and no later than four days after it is returned). It can also be helpful to include specific guidelines for what the grade appeal should include, and a clear outline of the process. For example, you could state that students should provide written justification for the appeal and include the assignment along with any relevant supplementary information. If a student has a dispute with a Teaching Assistant over a grade they have received, it can be helpful to make clear that they have the right to request a review by the professor and that an appeal will invoke a review of the full assignment and could result in an even lower grade.

Tools

When I teach these days, I bring a basket of fidget tools to class and place it at the front of the room. These tools are more commonly known as fidget toys, but I like to call them fidget tools not as some cutesy semantic trick but because I genuinely think that they can be tools for learning, thinking, and writing. Fidget tools are helpful devices that can release nervous energy and aid focus. Bringing fidget tools to class is one (easy) way to acknowledge that our students have bodies—a fact that seems too obvious to be stated but that often is disregarded in higher education. Providing fidget tools is one way in which we can normalize bodily movement in the classroom and acknowledge that our students have bodies that are part of their minds.

I introduce the fidget tools through this frame the first time I bring them to class and then invite students to experiment with different tools throughout the quarter. As they walk into the classroom, students can grab whatever tool they want and use it during class. I also tell students about what particular fidget tools have helped me in my writing and studying (most notably “the Tangle,” which I credit for still having cuticles after finishing my dissertation).

My fidget tool basket

Many teachers worry that fidget tools are childish distractions in the classroom. To alleviate that worry, I would like to share the results of an informal, anonymous survey that I conducted in two courses on academic writing at UCSB in Fall 2024. The students in these courses were Freshmen and Sophomores. Out of 42 students asked, 42 students answered “yes” to the question “Do you find the fidget tools helpful in class?” Only one student answered “yes” to the question “Do you find the fidget tools distracting in class?” (It should be noted that the same student also answered that they found the tools helpful). When asked to explain why they found the fidget tools helpful, students shared statements like these:

“The fidget tools have been very helpful, I get distracted really easily so the fidget tools help keep me focused instead of going on the internet and not paying attention.”

“I find that the fidget tools help make me less anxious.”

“I do find the fidgets helpful because I find myself not gravitating towards picking up my phone”

These are just a handful of examples of the overwhelming appreciation for these simple tools in the classroom. As seen in these comments, the tools can decrease anxiety, stress, and distracting pulls and help students focus on the class material. It is worth noting that several students mentioned that the fidget tools helped them avoid turning to their phones or computers during class time. Some students stated that they did not use the fidget tools because of fear of germs. None of these students found them distracting, however.

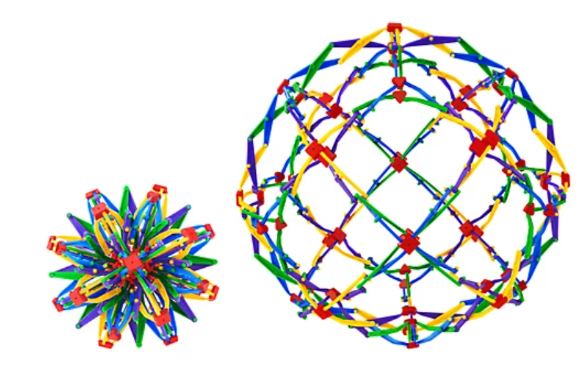

Below is a range of fidget tools that I have selected because they are relatively quiet. If you click on the image of a fidget, it will take you to a website where you can buy that particular tool. You may want to collaborate with your students to decide which tools work for you and your class. Speks.com has a range of fidgets that look more like tools and less like toys.

In my experience, bringing different tools to class and experimenting with varying practices is one way to make the UCSB classroom—with all its structural inequalities and practical flaws—work as well as possible for today’s students. And a classroom that works as well as possible for as many students as possible also tends to be a classroom that works (pretty) well for me as a teacher, in terms of both the quality of the work being done and the atmosphere in the room. “What works as well as possible” is of course never static or the same; rather, it will shift depending on the class, the teacher, the students, the subject, the room, and a variety of other factors. From a trauma-informed perspective, there are two constants, however: figuring out what works well depends upon me acknowledging what I don’t know about my students and their realities, and it calls for a willingness to adjust my teaching to these realities.

Additional practices

Below is a list of practices that were suggested to us at a Trauma-Informed Pedagogy Working Session that our project hosted in Spring 2024. I have not experimented with these practices (yet), which is why they have their own section here. We would like to thank everyone who participated in that session for sharing their insights and ideas so generously: Angela Andrade, Stephanie Batiste, Briana Conway-Miller, Jigna Desai, Jason Fly, Nolan Krueger, Mekhi Mitchell, Sharlene O’Brien, Julia Pennick, Michelle Petty-Grue, Matt Richardson, Kari Robinson, Maddie Roepe, Emiko Saldivar Tanaka, and Bob Samuels.

Peer teaching

Peer teaching can, for example, be done with the “jigsaw method,” where a class is given a set of questions or tasks, and then in small groups each handles a single question/task. Then, you rotate the groups and have students explain to a new group what they found or learned.

Language liberation

Including “language liberation” by incorporating one minute of silence into each class, potentially with bodily movement encouraged during this time. The point of this practice is to periodically liberate ourselves from the demands of language and to acknowledge that using academic discourse can be alienating.

Content description and options for engagement

Providing brief content descriptions of assigned readings and options for alternatives when the topics are likely to occasion high levels of anxiety or distress, such as:

submitting a written commentary but being excused from class discussion.

choosing a different text, submitting a commentary, and being excused from class discussion.

Somatic Experiencing

Training students in bodily (somatic) techniques that allow them to self-regulate when reading and discussing difficult material, such as:

teaching Somatic Experiencing and highlighting the representation of bodily experiences in literary texts.

Ways to promote comfort with dissensus

Viewing class as a space that teaches instructors and students to value and learn to live better with dissensus over consensus, for example by:

portraying texts as themselves contextual, thus necessitating “readings” from diverse perspectives.

crafting discussions and assignments that foreground associational logic: what set of adjectives, images, and worldviews do certain words, genres, and personages conjure?

emphasizing how what we know is intimately connected to who we know as a rationale for diversifying one’s reading and friendship circles.

Self grading

Students assign themselves a grade. This method often asks students to write an explanation of the grade they have assigned themselves and is most useful if you have time to hold individual meetings with each student to discuss the grade.

Peer grading

Students grade each other’s assignments, tests, or projects based on a rubric that the teacher has crafted (often in collaboration with the students). This method works best in courses where students have some familiarity with the subject already.

Notes

[1] This practice is inspired by Lars Stoltzfus’ “First Day of Class Introductions: Trans Inclusion in Teaching” in Trauma-Informed Pedagogies: A Guide for Responding to Crisis and Inequality in Higher Education, edited by Phyllis Thompson and Janice Carello, 2022, pp. 237–38.

[2] This practice is borrowed from Molly Wolf’s “Trigger Warning” in Trauma-Informed Pedagogies: A Guide for Responding to Crisis and Inequality in Higher Education, edited by Phyllis Thompson and Janice Carello, 2022, pp. 246–47.

[3] For research on the benefits of breaks, see e.g. Albulescu, Patricia et al. “"Give me a break!" A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of micro-breaks for increasing well-being and performance,” PloS one vol. 17, no. 8, e0272460, 2022 and Immordino-Yang, Mary Helen, et al. “Rest Is Not Idleness: Implications of the Brain’s Default Mode for Human Development and Education,” Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol. 7, no. 4, 2012, pp. 352–364.